The Great Depression was a worldwide economic crisis that in the United States was marked by widespread unemployment, near halts in industrial production and construction, and an 89 percent decline in stock prices. It was preceded by the so-called New Era, a time of low unemployment when general prosperity masked vast disparities in income.

The start of the Depression is usually pegged to the stock market crash of “Black Tuesday,” Oct. 29, 1929, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell almost 23 percent and the market lost between $8 billion and $9 billion in value. But it was just one in a series of losses during a time of extreme market volatility that exposed those who had bought stocks “on margin” – with borrowed money.

The stock market continued to decline despite brief rallies. Unemployment rose and wages fell for those who continued to work. The use of credit for the purchase of homes, cars, furniture and household appliances resulted in foreclosures and repossessions. As consumers lost buying power industrial production fell, businesses failed, and more workers lost their jobs. Farmers were caught in a depression of their own that had extended through much of the 1920s. This was caused by the collapse of food prices with the loss of export markets after World War I and years of drought that were marked by huge dust storms that blackened skies at noon and scoured the land of topsoil. As city dwellers lost their homes, farmers also lost their land and equipment to foreclosure.

President Herbert Hoover, a Republican and former Commerce secretary, believed the government should monitor the economy and encourage counter-cyclical spending to ease downturns, but not directly intervene. As the jobless population grew, he resisted calls from Congress, governors, and mayors to combat unemployment by financing public service jobs. He encouraged the creation of such jobs, but said it was up to state and local governments to pay for them. He also believed that relieving the suffering of the unemployed was solely up to local governments and private charities.

By 1932 the unemployment rate had soared past 20 percent. Thousands of banks and businesses had failed. Millions were homeless. Men (and women) returned home from fruitless job hunts to find their dwellings padlocked and their possessions and families turned into the street. Many drifted from town to town looking for non-existent jobs. Many more lived at the edges of cities in makeshift shantytowns their residents derisively called Hoovervilles. People foraged in dumps and garbage cans for food.

The presidential campaign of 1932 was run against the backdrop of the Depression. Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the Democratic nomination and campaigned on a platform of attention to “the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid.” Hoover continued to insist it was not the government’s job to address the growing social crisis. Roosevelt won in a landslide. He took office on March 4, 1933, with the declaration that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Roosevelt faced a banking crisis and unemployment that had reached 24.9 percent. Thirteen to 15 million workers had no jobs. Banks regained their equilibrium after Roosevelt persuaded Congress to declare a nationwide bank holiday. He offered and Congress passed a series of emergency measures that came to characterize his promise of a “new deal for the American people.” The legislative tally of the new administration’s first hundred days reformed banking and the stock market; insured private bank deposits; protected home mortgages; sought to stabilize industrial and agricultural production; created a program to build large public works and another to build hydroelectric dams to bring power to the rural South; brought federal relief to millions, and sent thousands of young men into the national parks and forests to plant trees and control erosion.

The parks and forests program, called the Civilian Conservation Corps, was the first so-called work relief program that provided federally funded jobs. Roosevelt later created a large-scale temporary jobs program during the winter of 1933–34. The Civil Works Administration employed more than four million men and women at jobs from building and repairing roads and bridges, parks, playgrounds and public buildings to creating art. Unemployment, however, persisted at high levels. That led the administration to create a permanent jobs program, the Works Progress Administration. The W.P.A. began in 1935 and would last until 1943, employing 8.5 million people and spending $11 billion as it transformed the national infrastructure, made clothing for the poor, and created landmark programs in art, music, theater and writing. To accommodate unions that were growing stronger at the time, the W.P.A. at first paid building trades workers “prevailing wages” but shortened their hours so as not to compete with private employers.

Roosevelt’s efforts to assert government control over the economy were frustrated by Supreme Court rulings that overturned key pieces of legislation. In response, Roosevelt made the misstep of trying to “pack” the Supreme Court with additional justices. Congress rejected this 1937 proposal and turned against further New Deal measures, but not before the Social Security Act creating old-age pensions went into effect.

Brightening economic prospects were dashed in 1937 by a deep recession that lasted from that fall through most of 1938. The new downturn rolled back gains in industrial production and employment, prolonged the Depression and caused Roosevelt to increase the work relief rolls of the W.P.A. to their highest level ever.

Hitler’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, following Japan’s invasion of China two years earlier and the continuing war there, turned national attention to defense. Roosevelt, who had been re-elected in 1936, sought to rebuild a military infrastructure that had fallen into disrepair after World War I. This became a new focus of the W.P.A. as private employment still lagged pre-Depression levels. But as the war in Europe intensified with France surrendering to Germany and England fighting on, ramped up defense manufacturing began to produce private sector jobs and reduce the persistent unemployment that was the main face of the Depression. Jobless workers were absorbed as trainees for defense jobs and then by the draft that went into effect in 1940, when Roosevelt was elected to a third term. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 that started World War II sent America’s factories into full production and absorbed all available workers.

Despite the New Deal’s many measures and their alleviation of the worst effects of the Great Depression, it was the humming factories that supplied the American war effort that finally brought the Depression to a close. And it was not until 1954 that the stock market regained its pre-Depression levels.

By Nick Taylor is the author of “American-Made,” a 2008 history of the Works Progress Administration.

http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/g/great_depression_1930s/index.html?inline=nyt-classifier&&&#

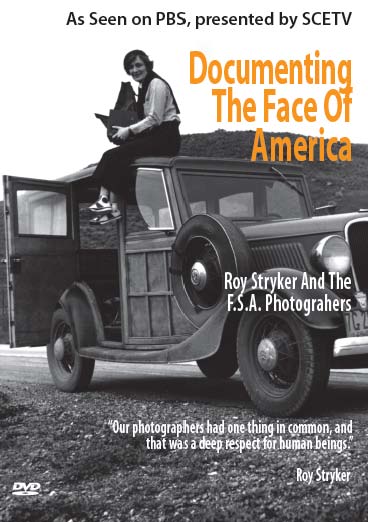

Poverty's Palette

The Depression, in Kodachrome: photographs from the Farm Security Administration and the Office of War Information, 1939-1943.