Recalling a Mission to Capture an Era’s Misery

“Migrant Mother,” Dorothea Lange’s image of a weathered, grimy Depression-era woman in California surrounded by her children, is one of the most famous photographs of the 20th century, as is “Fleeing a Dust Storm,” Arthur Rothstein’s shot of a farmer and his two young sons in the Oklahoma Dust Bowl whipped by the wind, a shack in the background.

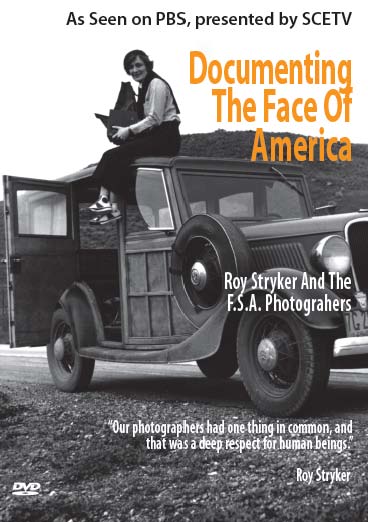

Arthur Rothstein’s “Fleeing a Dust Storm” is featured in “Documenting the Face of America,” Monday on most PBS stations. More Photos »

Multimedia

Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” introduced one segment of America to another. More Photos >

The politics and the photographers who shaped those images under the auspices of the federal Farm Security Administration come to life in “Documenting the Face of America: Roy Stryker and the F.S.A./O.W.I. Photographers,” an hourlong documentary on most PBS stations Monday night. The film shows how Mr. Stryker turned a small government agency’s New Deal project to document poverty into a visual anthology of thousands of images of American life in the 1930s and early ’40s that helped shape modern documentary photography; more than 160,000 are now at the Library of Congress.

Before television or the Internet, when many Americans lacked even a radio, the photographs told stories that would have remained elusive to those out of eyeball range. Ms. Lange and Mr. Rothstein, along with celebrated figures like Walker Evans and Gordon Parks, used their cameras to preserve scenes of winding bread lines, dirty-faced families in front of their ramshackle farmhouses or in jalopies with their possessions piled high, as well as the stark “colored” signs of segregated public facilities and somber black children picking cotton.

Mr. Stryker’s group of photographers “introduced Americans to America” and an entire generation to “the reality of its own time and place in history,” Mr. Stryker says in an interview heard on the program, which is narrated by Julian Bond, chairman of the N.A.A.C.P.

“I wanted to introduce a new generation to some of these photographs and the amazing stories that went with them,” said Jeanine Isabel Butler, who wrote and directed the film and produced it with her husband, Alastair Reilly, and her sister, Catherine Lynn Butler, in association with South Carolina ETV. Jeanine Isabel Butler is a writer and producer of documentary and educational films for PBS, the Discovery Channel and the National Geographic Channel among others.

Ms. Butler said that she was captivated by the idea of how a small-agency bureaucrat like Mr. Stryker, who kept a tight rein on his photographers and constantly wrangled more money for his work, managed to remain idealistic. Her team began working on the film in 2000, she said, and scored a coup along the way by interviewing Mr. Parks, one of the country’s most celebrated photographers, who died in 2006 at 93.

“I feel like some of the issues we were facing then continue to be issues we as a society face,” Ms. Butler said. “There are still racial and class differences that can inspire a whole new generation of filmmakers, artists and photographers to look and begin to capture. But it’ll never be a big government project again.”

F. Jack Hurley, professor emeritus of history at the University of Memphis and author of a book on Mr. Stryker, who died in 1975, said in an interview that “Documenting the Face of America” helped put a few dozen widely reproduced Depression-era photographs into a broader context. Mr. Hurley, who appears throughout the documentary, said it also showed that the photographs, now celebrated, were once denounced in some quarters as the Roosevelt administration’s political propaganda, meant to win favor for some of his New Deal initiatives.

“What we think of as social documentary, it starts here,” Mr. Hurley said in an interview. “Stryker started out showing rural poverty to well-off urban people but broadened the file to include the middle-class and even farmers faring well.” Mr. Stryker gave questions to the photographers to serve as guidelines for their work, Mr. Hurley said: What do people in small-town Texas do on a Saturday afternoon? How do people in Mississippi use their porches?

“You wind up with a nicely balanced portrait of America in the ’30s,” he said.

Mr. Stryker, heard on screen in a 1975 audio interview with Mr. Hurley, says he quickly realized that farmers in every area of the country were suffering. “The picture began to be the thing of my life,” he says. “The photograph was the way to reach the people. Somehow, some way, I wanted life in the pictures.”

“Documenting the Face of America” includes excerpts from Mr. Stryker’s letters and interview transcripts, and excerpts from the diaries and shooting scripts belonging to him and the photographers. It is chock-full of the most famous photographs of Ms. Lange and Mr. Rothstein, as well as Mr. Parks and Mr. Evans, Jack Delano, Russell Lee, Marion Post Wolcott, Ben Shahn and others.

Mr. Stryker, a World War I veteran and assistant professor of economics at Columbia University, went to work for the federal government in the summer of 1935, when the country was in the grip of the Great Depression. He directed the historical unit of the Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration). In the ’40s his photography unit was assigned to the Office of War Information, or O.W.I.

The initial assignment of the historical unit was to use photographs to try to persuade Congress that thousands of dispossessed farm families were in desperate need of government assistance.

Mr. Stryker had grown up on small dirt farm outside Montrose, Colo., and his father was “a prairie populist,” Mr. Hurley says in the film.

“Roy’s patriotism included the right to question the way things were done,” Mr. Hurley says in an on-camera interview. “And certainly by the 1930s he was very angry about the situation that poor farmers found themselves in and he really wanted to do something about it.”

Mr. Parks — whose work for Mr. Stryker produced “American Gothic,” the image of a black government cleaning woman standing in front of an American flag, a broom in one hand and a mop by her other side — talks about his first meeting with his boss soon after he arrived.

Mr. Stryker gave Mr. Parks an unusual assignment: leave the Farm Security Administration office at 14th Street and Independence Avenue and get lunch across the street. Then go across the street to a theater. There, in the heart of the capital, Mr. Parks found the “Whites Only” signs that barred his admission.

Mr. Parks, in an on-screen interview, recalls reporting his experiences to Mr. Stryker on his return to the office. “I said, ‘I think you know how it went.’ He says: ‘Yeah, I know how it went. Well, what are you going to do about it?’ I said: ‘I don’t know. What do I do about it?’ He said, ‘Well, what did you bring that camera down here for?’ ”

Although Mr. Stryker kept his photographers together through various political challenges, World War II changed everything, the film shows. His unit was moved to the Office of War Information, and he lost control of it. His photographers were asked to produce propaganda, like photographs that showed the supposedly fair treatment of the Japanese-Americans interned in wartime camps. But before resigning in 1943 Mr. Stryker appealed directly to the White House to keep the thousands of photographs together at the Library of Congress, where most remain.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/18/arts/television/18pbs.html

No comments:

Post a Comment